|

Shipwrecks, Sailors and 60,000 Years

Grim Crims and Convicts

Rotters and Squatters

Gold Graves and Glory

Swaggies and Diggers

Weevils, War and Wallabies

Rockin’ Rollin’ hair and Hippies

Booms Busts and Bushfires

‘These books cover Australian history as it’s never been written before- eight books that tell the ‘story’ of Australia, from the days of giant megafauna to the man indigenous nations, right up to 2010.’

Lavishly illustrated with Peter Sheehan’s hilarious cartoons, this is accessible history. Young people will glance through to laugh at the cartoons, be captured by the boxes of fascinating snippets, and then- often- go back and read the entire series.

Adults, too, may find this is the most readable (and comprehensive) history they have come across. Impeccably researched, mostly from primary sources instead of referring back to other history books, the Dinkum Histories covers everything from bushrangers to bushfires to how a drought helped to make us one nation.

|

Shipwreck, Sailors & 60,000 Years:

1770 and All that Happened Before Then

Telling it like it really was - true-blue Aussie history!

The Indigenous people of Australia have lived here for tens of thousands of years. They survived the ice age and ancient global warming. They saw oceans sink and oceans rise. They watched the mega-beasts disappear and dingoes arrive. Theirs is the oldest civilisation in the world.

Then along came the Dutch. And the Portuguese. And the British. Things would never be the same again.

Come with Jackie French and Peter Sheehan on a voyage back through time. It's history as you've never seen it.

|

Grim Crims and Convicts

It was an incredible idea - to found a colony of convicts eight months' sail away from Great Britain. In a land with no cities, no farms, no rich spices. Just savage huts. No country had ever thought to send a colony so far away. Why on earth would you bother?

Cannibal convicts, murdering squatters, sea captains who kidnapped their crew, poor farmers forced off their land- they had all come to the colonies of New South Wales and Van Dieman's land to make better lives for themselves. And now there were new colonies and farms spreading around Australia.

|

Rotters and Squatters

There were two tiny colonies at the end of the world-one in New South Wales and one in Van Diemen?s Land-perched on the edge of a vast and mostly unmapped continent. There were four main towns-Sydney and Parramatta in New South Wales, and Hobart and Launceston in Van Diemen?s Land. Radiating out from around these towns were a growing number of smaller villages.

|

Gold, Graves and Glory

For 60,000 years the rest of the world had pretty much left Australia and its Aboriginal nations alone. Then it became a home for Britain?s criminals and poor. Now a con man had found gold and suddenly everyone was heading to Australia: adventurers, revolutionaries, camels ? Australia would never be the same.

|

A Nation of Swaggies and Diggers

The Australian colonies had come a long way since they were a dump for grim crims and convicts. Life was comfortableat least for some. But soon drought would send swaggies waltzing their matildas along the roads, and bad times would make politicians dream of uniting the country into one nation. And then a far-off war would create a different kind of digger. What they brought back home would make greater changes to Australia than gold ever did. Meet the scabs and the swaggies, battling politicians, doddering generals, sheep stealers and heroic diggers who finally turned us into a nation in the latest instalment of the Fair Dinkum Histories. Its history as youve never seen it!

|

Weevils, War and Wallabies

1920-1945, an iconic period in Australian history: QANTAS founded, the Sydney Harbour Bridge built, Phar Lap wins the Melbourne Cup and dies in the US, Don Bradman wows the world at the wicket and becomes the main target in the Bodyline series. The Depression hits. Australia enters WW II. Aborigines lobby for full citizenship. German ships lay mines off the Australian coast and the Japanese attack Australia. History comes to life!

|

Rockin', Rollin', Hair and Hippies

World War II was over, and it was a good time to be Australian. Rock ?n? roll, television and the Olympics had come Down Under. But underneath it all was the menace of the Cold War, and then came the horrors of Korea and Vietnam. Why couldn?t we all just get along? Covers a pivotal time in Australia?s history, as ideologies clashed and a new national identity was evolving.

|

Booms, Busts and Bushfires

Entertaining and amusing, with wide appeal. Facts for kids you?ll not find anywhere else. Aussie history from 1973 to now. Telling it like it really was-true-blue Aussie history! Australia had changed before, but slowly. Now everything was fast! Attitudes were evolving, technology was changing every aspect of life, and people were starting to recognise the damage we were doing to our land-and the way Australia?s Indigenous people had been mistreated.

Our resources had made us a rich country, but how long could the good times last? Join the fireys, goths, yuppies and greenies for the final instalment of the Fair Dinkum Histories. It?s history as you?ve never seen it!

|

The Fascinating History of Your Lunch (Harper Collins)

The history of the world is in your lunch box!

Who were the first farmers...where did pizza come from..and icecream...and why weren't olden days kids allowed to drink fruit juice?

A hilarious but insightful look at the most interesting part of civilization- it's food!

|

To the Moon and Back (Harper Collins)

Who are the Honeysuckle Creek mob? And how did they assist the first moon landing?

When man took the first step on the moon it was a bunch of Australian technicians who tracked the spacecraft and sent the first television pictures to the world. No, not at Parkes - the movie The Dish got it wrong. They were from Honeysuckle Creek in the ACT.

This is their story, told by Bryan Sullivan, one of the technicians on duty at the time, and his wife, children's author Jackie French.

You can see images

from the book's launch at Honeysuckle Creek here.

|

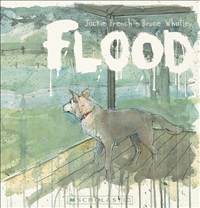

Flood, and its Beginnings

I grew up in Brisbane, in houses on stilts with big verandas. Each year floods would surround us, water like café latte, thick with foam. We kids would dangle our feet over the veranda, and watch the cars screech to a stop at the floodwater.

Floods in those days were a break from school, the adventure of forming a human chain to haul my mother’s mini minor car back when it floated down the street (We tied it to the peach tree where it floated happily till the flood subsided.)

It never occurred to us to be scared of floods. Every house we knew was built out of flood reach, and we all knew which streets that would turn into rivers when the tail of a cyclone whipped past, crashing corrugated iron and garbage bins against the fences.

The first I knew of the 2011 Queensland floods was the call from a friend’s mother, in Townsville. She had just outraced a wall of water, frantically reversing her car and screaming to try to warn those still heading towards the floodwater. She cried as she said ‘They didn’t stop. None of them stopped!’ She had grown up with floods. They hadn’t. They didn’t know the savagery of water.

The 2011 floods swept into unprepared towns. Land had been cleared, so the water gained speed. Houses had been built on flood plains, labelled ‘never to be built on’ in my childhood, but homes and gardens now.

My father was frail, living next to the river, cut off by floodwater. He watched from his veranda as that tiny tugboat pushed and shoved the walkway out to sea. If it hadn’t, his home might have been swept away, and him as well. All I could do was stay on the phone, as he sat on his veranda and watched the river rise.

Dad was always a story teller, and I can still hear his voice showing me the dramas, hour by hour: the police rescue boat racing after a family stranded on an out of control houseboat, the café that floated past, still with the tables set for lunch.

Dad died before the book was printed, but I still hear his voice on every page.

My brother provided shelter to other families whose homes were under water. The power might have been off but the BBQ gas bottles were full, and when they rang to say they were safe I could hear laughter in the background.

My nieces cooked and cooked. Another niece, a nurse, helped care for a dementia ward, as well as those who came to the nursing home for shelter. They were cut off for about 36 hours, and no other nurses could get in to relieve them. They kept on going. As she said, it’s just what you have to do.

As the water receded my brother and nephew joined thousands of others with mops, spades and hoses. My nieces kept cooking for the clean up, linking via the Internet with others to keep all the volunteers fed.

More than 60,000 volunteers registered that first day. Probably double that number just turned up. But the most extraordinary thing was that none thought of themselves as heroes. They just did what was needed- and did it with jokes and laughter too. It was so very, very Australian.

After Hurricane Katrina they locked the survivors in football stadiums. Australians held barbeques, cooked chocolate chip biscuits, and then got out the mops and shovels.

I was proud to be part of my family in those weeks. I felt and proud to be Australian, too.

The flood was still snaking through the streets when Andrew Berkut from Scholastic rang me and told me I had to write the book. And so I did, in ten days, instead of the three years a book usually takes. Bruce worked with the same urgency, and when I saw the strength and beauty of his work I cried again.

Had we captured it? My hand shook as I gave the first copy to my brother. He had been there. I hadn’t. He looked it and said ‘I’d already forgotten what it was like. It’s a good book, Jacq. It’s important that we remember this.’

Bruce and I were even more apprehensive about the reaction of kids who had lost homes and teddy bears in the flood. We had hoped to show that bad things happen, but that they pass too- and if you look, there are those who’ll help. But when we finally showed the children the book, on the morning of the launch, a small boy just touched one of Bruce’s extraordinary pages and said ‘I’d forgotten the flood was that colour.’ By the time I had finished reading the book, they were smiling.

I think- I hope- that when kids read Flood they’ll remember the matter of fact heroism, the strength of hands that helped and offered hope, and not the terror of dark water that rose unstoppable in the night.

|

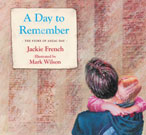

A Day to Remember

The Day We Remember

The barges, lifeboats and rowing boats set out from the big ships before dawn on April 25, almost a hundred years ago. As the sky grew grey, the first men of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps landed on a narrow strip of Turkish beach.

Over the next six months a legend grew of heroes who advanced no matter what the odds; of mates who shared their last crust with a friend; of ‘diggers’ who refused to salute an officer, who died with a last joke and a grin.

The stories left out a lot that didn’t fit the image. But it was also true.

The first Anzac day in 1916 was created to urge more men to feed the war. A Day to Remember is the history of that one day of the year, and how it has changed over almost 100 years. It’s the story of Australia, too.

My father in law landed at Anzac Cove, too. He never spoke of it.* Every year he marched, increasingly bitter, with friends unemployed because of the depression, or with lungs or eyes rotted from mustard gas. The marches were mostly men only affairs back then, as were the dawn services, in case crying women disturbed the silence.

My childhood saw the battered and weary of World War two, men scarred in body and mind from Japanese prison camps or the Burma railway, the mothers of my friends and my violin teacher, who had survived concentration camps.

Boys of my own generation marched away as conscripts to Vietnam, while I walked in anti war demonstrations. As a historian I came up against determinedly uncooperative bureaucracy as I tried to check a list of places where Australian troops have been sent since the 1970’s#. While newspapers talk of Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan, few Australians know our defense forces serve as peacekeepers places like Tonga, Cambodia, Somalia and Rwanda and Haiti. Peace is not easily won, or kept. But many do the best they can.

I’ve seen Anzac Day change from the grim faced marchers of my childhood, to the years when it seemed as if Anzac day might vanish except for a dedicated few, or when the Anzac day marchers faced anti conscription demonstrations, and women with placards who demanded the right to march too. In the past two decades our reawakening sense of history has recreated Anzac day yet again. Each year the marches are larger, the commemorations broader. Anzac Day itself has been a catalyst for many people to discover Australian’s history, too.

Last Anzac day I stood with friends in Braidwood’s main street. Children marched with their grandparents’ medals. A poodle sat next to us, a sprig of rosemary in its collar. A kid called out ‘Daddy’ as her father passed. Most of us, I think, wept a little as the Last Post played.

And we remembered.

For some it was a celebration of military tradition. Others in the crowd were pacifists, or felt that Australians shouldn’t be in Afghanistan. It didn’t matter. There are many different memories that make up Anzac day now. We remembered fathers, husbands, aunts, sons, daughters and grandfathers; those who our country sent to war and then forgot, when they returned home damaged; the starving and tortured who struggle towards refugee camps; all who suffer in war, or give their lives to try to make things better.

I wrote A Day to Remember because by honouring the suffering and sacrifice of others we find the gift of empathy ourselves. On this one day of the year, it is good to stand together, and remember not just the past, but why we need to remember, too.

*For those trying to calculate my husband’s age: Jack Sullivan survived Gallipoli and World War 1, though probably never quite recovered. He married and had children late in life.

# The six months of attempts to get two short paragraphs of already public information approved as accurate by the Department of Defence for a history series for kids would take at least three pages to describe. |